References

1.Martina, B.E.E., Koraka, P. and Osterhaus, A.D.M. (2009), “ Dengue virus pathogenesis : an integrated view, ” Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 22 (4), 564-581.

Publisher – Google Scholar

2.Guha-Sapir, D. and Schimme,r B (2005), “ Dengue fever : new paradigms for a changing epidemiology, ” Emerging Themes in Epidemioogyl, 2 (1), 1.

Google Scholar

3.Guzma”²n, M.G. and Kouri, G (2003), “ Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever in Americas :lessons and challenges, ” Journal of Clinical Virology, 27 (1), 1-13.

Publisher – Google Scholar

4. Bhatt, S., Gething, P.W., Brady, O.J., Messina, J.P., Farlow, A.W., Moyes, C.L., et al (2013),

“ The global distribution and burden of dengue, ” Nature, 496 (7446) : 504-507.

Google Scholar

5. Halstead, S.B (2007), “ Dengue, ” Lancet 370 (9599), 1644-1652.

Publisher – Google Scholar

6. Ong, A., Sandar, M., Chen, M.I. and Sin, L.Y (2007), “ Fatal dengue hemorrhagic fever in adults during a dengue epidemic in Singapore, ” International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 11 (3),263-267.

Publisher – Google Scholar

7. Di”²az-Quijano F.A. and Waldman E.A. (2012), “ Factor associated with dengue mortality in LatinAmerica and Caribbean, 1995-2009 : an ecological study, ” American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 86 (2), 328-334.

Publisher – Google Scholar

8. UNICEF, UNDP, World Bank, WHO. Evaluating diagnostics-Dengue : a continuing global threat. (Retrieved January 8, 2014), http://www.nature.com/reviews/micro

9. Kouri, G.P., Guzma”²n, M.G. and Bravo, J.R (1987), “ Why dengue hemorrhagic fever in Cuba? 2.An integral analysis, Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 81 (5), 821-823.

10. Halstead, S.B., Nimanitaya, S. and Cohen, S.N (1970), “ Observations related to pathogenesis of dengue hemorrhagic fever : Relation of disease severity to antibody response and virus recovered, ” Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 42 (5), 311-328.

Google Scholar

11. Lee, M.S., Hwang, K.P., Chen, T.C., Lu, P.L. and Chen, T.P (2006), “ Clinical characteristics of dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever in a medical center of southern Taiwan during the 2002 epidemic, ” Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection, 39 (2), 121-129.

Google Scholar

12. Po”²voa, T.F., Alves, Ada.M.B., Oliveira, C.A.B., Nuovo, G.J., Chagas, V.L.A. and Paes, M.V.P

(2014), “ The pathology of severe dengue in multiple organs of human fatal cases : histopathology, ultrastructure and replication, ” PLoS ONE, 9 (4), e83386. DOI :10.1371/jpournal.pone.0083386

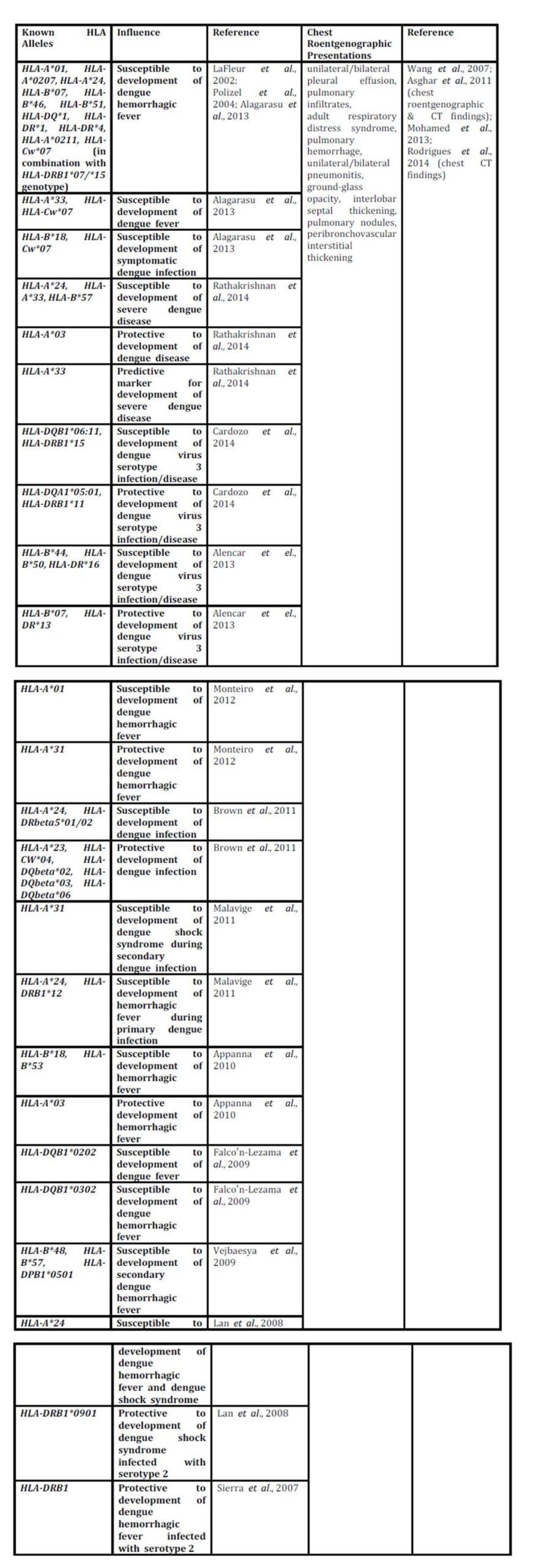

13. Stephens, H.A., Klaythong, R., Sirikong, M., Vaughn, D.W., Green, S., Kalayanarooj, S., et al (2002), “ HLA-A and HLA-B allele associations with secondary dengue virus infections correlate with disease severity and the infecting viral serotype in ethnic Thais, ” Tissue Antigens, 60 (4), 309-318.

Publisher – Google Scholar

14. LaFleur, C., Granados, J., Vargas-Alarcon, G., Ruiz-Morales, J., Villarreal-Garza, C., Hiqueral, L., et al (2002),

“ HLA-DR antigen frequencies in Mexican patients with dengue virus infection : HLA- DR4 as a possible genetic resistance factor for dengue hemorrhagic fever, ” Human Immunology, 63 (11), 1039-1044.

Google Scholar

15. Loke, H., Bethell, D.B., Phuong, C.X., Dung, M., Schneider, J., White, N.J., et al (2002), “ Strong HLA class I-restricted T-cell responses in dengue hemorrhagic fever : a double-edged sword ? ” Journal of Infectious Diseases, 184 (11), 1369-1373.

16. Sakuntabhai, A., Turbpaiboon, C., Casade”²mont, I., Chuansumrit, A., Lowhoo, T., Kajaste-Rudnitski, A., et al (2005), “ A variant in CD209 promoter is associated with severity of dengue disease, ” Nature Genetics, 37 (5), 507-513.

Publisher – Google Scholar

17. Fernandez-Mastre, M.T., Gendzekhadze, K., Rivas-Vetencourt, P. and Layrisse, Z (2004), “ TNF-α-308A allele, a possible severity risk factor of hemorrhagic manifestation in dengue fever patients, ” Tissue Antigens, 64 (4), 469-472.

Publisher – Google Scholar

18. Kalayanarooj, S., Gibbons, R.V., Vaughn, D., Green, S., Nisalak, A., Jarman, R.G., et al (2007), “ Blood group AB is associated with increased risk for severe dengue disease in secondary infections, ” Journal of Infectious Diseases, 195 (7), 1014-1017.

Publisher – Google Scholar

19. Rico-Hesse, R (1990), “ Molecular evolution and distribution of dengue viruses type 1 and 2 in nature, ” Virology, 174 (2), 479-493.

Publisher – Google Scholar

20. Rico-Hesse, R., Harrison, L.M., Salas, R.A., Tovar, D., Nisalak, A., Ramos, C., et al (1997),

“Origins of dengue type 2 viruses associated with increased pathogenicity in the Americas, ” Virology, 230 (2), 244-251.

Google Scholar

21. Rodriguez-Roche, R.M., Alvarez, M., Gritsun, T., Halstead, S., Kouri, G., Gould, E.A., et al (2005),

“ Virus evolution during a severe dengue epidemic in Cuba, 1997, ” Virology, 334 (2), 154-159.

Publisher – Google Scholar

22. Guzma”²n, M.G., Kouri, G., Bravo, J., Valdes, L., Vazquez, S. and Halstead, S.B (2002), “ Effect of age on outcome of secondary dengue 2 infections, ” International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 6 (2), 118-124.

Publisher – Google Scholar

23. Cologna, R. and Rico-Hesse, R (2003), “ American genotype structures decrease dengue virus output from human monocytes and dendritic cells, ” Journal of Virology, 77 (7), 3929-3938.

Publisher – Google Scholar

24. Leitmeyer, K.C., Vaughn, D.W., Watts, D.M., Salas, R., Villalobos, I., Chacon, de, et al (1999),

“Dengue virus structural differences that correlate with pathogenesis, ” Journal of Virology, 73 (6), 4738-4747.

Google Scholar

25. Jessie, K., Fong, M.Y., Devi, S., Lam, S.K. and Wong. K.T (2004), “ Localization of dengue virus in naturally infected human tissues, immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization, “Journal of Infectious Diseases, 189 (8), 1411-1418.

Publisher – Google Scholar

26. Paes, M.V., Pinhao, A.T., Barreto, D.F., Costa, S.M., Oliveira, M.P., Nogueira, A.C., et al (2005),

“ Liver injury and viremia in mice infected with dengue-2 virus, ” Virology, 338 (2), 236-246.

Google Scholar

27. Seneviratne, S.L., Malavige, G.N. and de Silva, H.J (2006), “ Pathogenesis of liver involvement during dengue viral infections, ” Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 100 (7), 608-614.

Publisher – Google Scholar

28. Nkhoma, E.T., Poole, C., Vannappagari, V., Hall, S.A. and Beutler, E (2009),

“ The global prevalence of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency : a systematic review and meta-analysis, ” Blood Cells Molecules and Diseases, 42 (3), 267-278.

Google Scholar

29. Wu, Y.H., Tseng, C.P., Cheng, M.L., Ho, H.Y., Shih, S.R. and Chiu, D.T (2008),

“ Glucose-6- phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency enhances human coronavirus 229E infection, ” Journal ofInfectious Diseases, 197 (6), 812-816.

Google Scholar

30. Zivna, I., Green, S., Vaughn, D.W., Kalayanarooj, S., Stephens, H.A., Chandanayingyong, D., et al

(2002), “ T-cell responses to an HLA-B*07-restricted epitope on the dengue NS3 protein correlate With disease severity, ” Journal of Immunology, 168 (11), 5959-5965.

Google Scholar

31. Polizel, J.R., Bueno, D., Visentainer, J.E., Sell, A.M., Borelli, S.D., Tsuneto, L.T., et al (2004), “Association of human leukocyte antigen DQ1 and dengue fever in a white Southern Brazilian population, ” Memo”²rias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, 99 (6), 559-562.

Publisher – Google Scholar

32. Alagarasu, K., Mulay, A.P., Sarikhani, M., Rashmika, D., Shah, P.S. and Celilia, D (2013), “ Profile of human leukocyte antigen class I alleles in patients with dengue infection from Western India, ” Human Immunology, 74 (12), 1624-1628.

Publisher – Google Scholar

33. Malavige, G.N., Fernando, S., Fernando, D.J. and Seneviratne, S.L (2004), “ Dengue viral infection, ” Postgraduate Medical Journal, 80 (948), 588-601.

Publisher – Google Scholar

34. Rathakrishnan, A., Klekamp, B., Wang, S.M., Komarasamy, T.V., Natkunam, S.K., Sanchez-Anguiano, A, et al (2014), “ Clinical and immunological markers of dengue progression in a study cohort from a hyperendemic area in Malaysia, ” PLoS ONE, 9 (3), e92021. DOI : 10.1371/journal.pone.0092021

Publisher – Google Scholar

35. Cardozo, D.M., Moliterno, R.A., Sell, A.M., Guelsin, G.A.S., Beltrame, L.M., Clemintino, S.L., et al (2014), “ Evidence of HLA-DQB1 contribution to susceptibility of dengue serotype 3 in dengue patients in southern Brazil, ” Journal of Tropical Medicine, Article ID 968262, 6 pages.

Publisher – Google Scholar

36. Alencar, L.X.E.de, Braga-Neto, U.deM., Nascimento, E.J.M.do, Cordeiro, M.T., Silva, A.M., Brito, A.A.de, et al (2013), “ HLA-B*44 is associated with dengue severity caused by DENV-3 in a Brazilian population, ” Journal of Tropical Medicine, Article ID 648475, 11 pages.

Publisher – Google Scholar

37. Monteiro, S.P.,Brasil, P.E.A.A.do, Cabello, G.M.K., Souza, R.V.de, Brasil, P., Georg, I., et al (2012),

“ HLA-A*01 allele : a risk factor for dengue hemorrhagic fever in Brazil’s population, ” Memo”²rias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, 107 (2), 224-230.

Publisher – Google Scholar

38. Brown, M.G., Salas, R.A., Vikers, I.E., Heslop, O.D. and Smikle, M.F (2011), “ Dengue HLA associations in Jamaicans, ” West Indian Medical Journal, 60 (2), 126-131.

Publisher – Google Scholar

39. Malavige, G.N., Rostron, T., Rohanachandra, L.T., Jayaratne, S.D., Fernando, N., Silva, A.D.De, et al (2011),

“ HLA class I and class II associations in dengue viral infections in a Sri Lankan population, ” PLoS ONE, 6 (6), e20581. DOI : 10.1371/journal.pone.0020581

Publisher – Google Scholar

40. Appanna, R., Ponnampalavanar, S., See, L.L.C. and Sekaran, S.D (2010), “ Susceptible and protective HLA class 1 allele against dengue fever and dengue hemorrhagic fever patients in a Malaysian population, ” PLoS ONE, 5 (9), e13029. DOI : 10.1371/journal.pone.0013029

Publisher – Google Scholar

41. Falco”²n-Lezama, J.A., Ramos, C., Zuñiga, J., Jua”²rez-Palma, L., Rangel-Flores, H., Garcia-Trejo, A.R., et al (2009), “ HLA class I and II polymorphisms in Mexican Mestizo patients with dengue fever, ” Acta Tropica, 112 (2), 193-197.

Publisher – Google Scholar

42. Vejbaesya, S., Luangtrakool, P., Luangtrakool, K, Kalayanarooj, S., Vaughn, D.W., Endy, T.P., et al (2009),

“ TNF and LTA gene, allele, and extended HLA haplotype associations with severe dengue virus infection in ethnic Thais, ” Journal of Infectious Diseases, 199 (10), 1442-1448.

Publisher – Google Scholar

43. Lan, N.T.P., Kikuchi, M., Huong, V.T.Q., Ha, D.Q., Thuy, T.T., Tham, V.D., et al (2008), “ Protective and enhancing HLA alleles, HLA-DRB1*0901 and HLA-A*24, for severe forms of dengue virus infection, dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome, ” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2 (10), e304. DOI : 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000304

Publisher – Google Scholar

44. Sierra, B., Alegre, R., Pe”²rez, A.B., Garcia, G., Sturn-Ramirez, K., Obasanjo, O., et al (2007), “ HLA-A, -B, -C, and -DRB1 allele frequencies in Cuban individuals with antecedents of dengue 2 disease : advantages of the Cuban population for HLA studies of dengue virus infection, ” Human Immunology, 68 (6), 531-540.

Publisher – Google Scholar

45. Likitnukul, S., Prappal, N., Pongpunlert, W., Kingwatanakul, P. and Poovorawan, Y (2004), “ Dual infections : dengue hemorrhagic fever with unusual manifestations and mycoplasma pneumonia in a child, ” Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health, 35 (2), 399-402.

Publisher – Google Scholar

46. Ali, F., Saleem, T., Khalid, U., Mehwood, S.F. and Jamil, B (2010), “ Crimen-Congo hemorrhagic fever in a dengue-endemic region : lessons for the future, ” Journal of Infection in Developin Countries, 4 (7), 459-463.

Publisher – Google Scholar

47. Wang, C.C., Wu, C.C., Liu, J.W., Lin, A.S., Liu, S.F., et al (2007), “ Chest radiographic presentation in patients with dengue hemorrhagic fever, ” American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 77 (2), 291-296.

Publisher – Google Scholar

48. Mohamed, N.A., El-Raoof, E.A. and Ibraheem, H.A (2013), “ Respiratory manifestations of dengue fever in Taiz-Yemen, ” Egypt Journal of Chest Diseases and Tuberculosis, 62 (NA), 319-323.

Publisher – Google Scholar

49. Asghar, J. and Farooq, K (2011), “ Radiological appearance and their significance in the management of dengue hemorrhagic fever, ” Pakistan Journal of Medical and Health Sciences, 5 (4), 685-692.

Publisher – Google Scholar

50. Rodrigues, R.S., Brum, A.L.G., Paes, M.V., Po”²voa, T.F., Basilio-de-Oliveira, C.A., Marchiori, E., et al (2014), “ Lung in dengue : computed tomography findings, ” PLoS ONE, 9 (5), e96313. DOI : 10.1371/journal.pone.0096313

Publisher – Google Scholar

51. Duchin, J.S., Koster, F.T., Peters, C.J., Simpson, G.L., Tempest, B., Zaki, S.R., et al (1994),

“ The Hantavirus Study Group. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome : a clinical description of 17 patients with a newly recognized disease, ” New England Journal of Medicine, 330 (14), 949-955.

Publisher – Google Scholar

52. Castillo, C., Naranjo, J., Sepu”²lveda, A., Ossa, G. and Levy, H (2001), “ Hantavirus pulmonary

syndrome due to Andes virus in Temuco, Chile : clinical experience with 16 adults, ” Chest, 120 (2), 548-554.

Publisher – Google Scholar

53. Vapalahti, O., Mustonen, J., Lundkvist. A., Henttonen, H., Plyusnin, A. and Vaheri, A (2003),

“Hantavirus infections in Europe, ” Lancet Infectious Diseases, 3 (10), 653-661.

Publisher – Google Scholar

54. Rasmuson, J., Pourazar, J., Linderholm, M., Sandström, T., Blomberg, A. and Ahlm, C (2011),

“Presence of activated airway T lymphocytes in human Puumala hantavirus disease, ” Chest, 140 (3), 715-722.

Publisher – Google Scholar

55. Guirakhoo, F., Kitchener, S., Morrison, D., Forrat, R., McCarthy, K., Nicholas, R., et al (2006),

“Live attenuated chimeric yellow fever dengue type 2 (ChimeriVax-DEN2) vaccine : Phase I clinical trial for safety and immunogenicity : effect of yellow fever pre-immunity in induction of cross neutralizing antibody responses to all 4 dengue serotypes, ” Human Vaccine, 2 (2), 60-67.

Publisher – Google Scholar

56. Durbin, A.P., Whitehead, S.S., McArthur, J., Perreault, J.R., Blaney, J.E. Jr., Thumar, B., et al (2005),

“ rDEN4 delta 30, a live attenuated dengue virus type 4 vaccine candidate, is safe, immunogenic, and highly infectious in healthy adult volunteers, ” Journal of Infectious Diseases, 191 (5), 710-718.

Publisher – Google Scholar

57. Raviprakash, K., Apt, D., Brinkman, A., Skinner, C., Yang, S., Dawes, G., et al (2006), “ A chimeric tetravalent dengue DNA vaccine elicits neutralizing antibody to all four virus serotypes in rhesus macaques, ” Virology, 353 (1), 166-173.

Publisher – Google Scholar

58. Hermida, L., Bernardo, L., Martin, J., Alvarez, M., Prado, I., Lo”², C., et al (2006), “ A recombinant fusion protein containing the domain III of the dengue-2 envelope protein is immunogenic and protective in nonhuman primates, ” Vaccine, 24 (16), 3165-3171.

Publisher – Google Scholar

59. Whitehead, S.S., Falqout, B., Hanley, K.A., Blaney, J.E. Jr., Markoff, L. and Murphy, BR (2003),

“ A live, attenuated dengue virus type 1 vaccine candidate with a 30-nucleotide deletion in the 3”² untranslated region is highly attenuated and immunogenic in monkeys, ” Journal of Virology,77 (2), 1653-1657.

Publisher – Google Scholar

60. Edelman, R., Wasserman, S.S., Bodison, S.A., Putnak, R.J., Eckels, K.H., Tang, D., et al (2003),

“ Phase I trial of 16 formulations of a tetravalent live-attenuated dengue vaccine, ” American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 69 (6 Suppl), 48-60.

Publisher – Google Scholar