Introduction

The importance of mastering a specific set of competencies for any given jobs has been well documented in the literature. It is because of this reason that researchers have developed various competencies models and framework for various kinds of professions (e.g. Vakola, Soderguist & Prastacos, 2007; Schroeter, 2008; Yaszay et al, 2009). According to Griffiths & King (1985), competency is the generic knowledge, skills and attitude of a person related to affective behavior as showed through performance.

Within the library and information management field, various studies have investigated the required competencies of the professional librarians (e.g. Abriza, 1998; Zaiton et al., 2004). Providentially, the findings of these studies have helped to further deepen our understanding of the topic. However, upon further scrutiny, most of these studies have focused on professional librarians. Very few studies have attempted to explore the required competencies among para-professionals of the library services. Questions on whether their required competencies are comparable to professional librarians seem to be unanswered. To this effect, this paper reports the findings of a study which was conducted with a view to identifying the required competencies among para-professionals in the library services.

Literature Review

Para-Professional in Library Services

Para-professionals in the library services are library associates, library technicians, or library assistants who assist the professional librarians in library-related task. The duties performed by them include database management, cataloguing, ready reference and serials and monograph processing. In terms of qualifications, the para-professionals of the library services usually hold college diplomas but not library-related degrees. Within the context of the Malaysian government public services (inclusive of the Malaysian State Government), para-professionals in the public libraries are those staffs holding the post of “Assistant Library Officer”; “Senior Assistant Library Officer”; “Library Attendant” and “General and “General Assistant”.

Competencies

Competencies have been defined as the interplay of knowledge, understanding, skills and attitudes required to do a job effectively from the point of view of both the performer and the observer (Murphy, 1991). The Federal Library and Information Centre Committee Library of Congress or FLICC (2008) defines competencies as the knowledge, skills and abilities that define and contribute to performance in a particular profession. Knowledge refers to having information about; knowing or understanding something; skill is the ability to apply knowledge effectively and attitude refers to the individual’s mental or emotional approach to something. One can distinguish between professional competencies which are generic skills, attitudes and values.

Helmick and Jaguszewski (2006) suggest that in personal career development terms, competencies can also be thought of as flexible knowledge and skills that allow the librarian to function in a variety of environments and to produce a continuum of value-added, customized information services that cannot be easily duplicated by others. At a time when professionals in all fields are being encouraged to invest in themselves and to prepare for employment as independent contractors, it is critical that librarians define their competencies and that they continue to improve the range of professional and personal competencies that will form the basis for their future careers.

The Competencies Standards of Librarianship

The importance of competencies standard has been well advocated in the literature. For instance, Eells & Jaguszewski (2008) and Kenny (2008) identified the importance of these competencies standards as (i) creating a common bond of understanding and a common language for defining professional standards, (ii) competencies are the foundation for competency-based management and continuous process improvement ensuring that librarians have the knowledge, skills and abilities to accomplish mission requirements, (iii) they can be used as tools to design and develop training and educational programs, position descriptions and performance evaluation instruments and for alignment with strategic objectives.

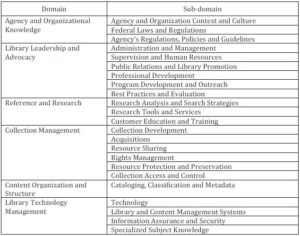

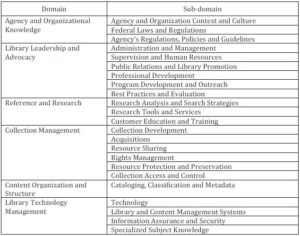

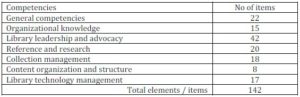

Within the library profession, currently, there are two professional competencies standards namely the ALA’s Core Competencies of Librarianship (American Library Association, 2009) and the Federal Librarian Competencies (Library of Congress, 2008). Between the two, the later is considered more comprehensive compared to the later as it is more comparable to the various competencies model, such as Management Competency Model; Holistic Competency Model and Professional Competency Model (Lester, 1995; Cheetham & Chivers, 1996; Vitala, 2005). Table 1 presents the domain and sub-domain of the Federal Librarian Competencies.

Table 1: ALA’s Core Competencies of Librarianship and Federal Librarian Competencies Standards

Previous Studies on Required Competencies

Mining the literature unveiled that various studies have been carried out to investigate the training needs of the professionals and para-professionals in the library services. These studies are: Cronin (1983); Goulding et.al. (1999); Musher (2001); Braun (2002); Soo (2005) and Ashcroft (2004). These studies have employed various methodologies, some of which were surveys, interviews and focus groups discussions. Due to the descriptive nature of the knowledge, skills and abilities of the professionals and para-professionals employed in the libraries, survey questionnaires together with face-to-face interviews were the most frequently employed as seen in studies by Buttlar & Du Mont (1996); Soo (2005); Griffiths (2005); Krissof & Konrad (2005); Lou (2007); Rice-Lively & Racine (2008). One of the aims of the studies was identification of competencies needed by the librarians and information professionals in the new millennium.

In the context of Malaysia, there are three previous studies carried out on competencies of librarians. Abriza’s study (1998) examined the role of teacher librarians in secondary schools as perceived by three groups of people directly involved in school librarianship – teacher librarians, library educators and education officers. Her study aimed at determining the essential competencies and the education required for teacher librarians to perform their role. In 2004, the National Library of Malaysia conducted a study to identify the gaps between the present knowledge and skills, and those required for excellent performance by the professionals and para-professionals employed by the National Library. One of the aims of the study was to design training and development plan of those involved. On the other hand, Zaiton et al. (2004) examined the manpower needs of professionals and non-professionals in the libraries of Malaysia.

Research Methodology

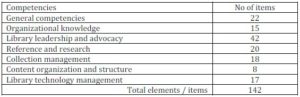

The conduct of this study involves the use of survey research methodology. A questionnaire was developed and used to collect the research data. The instrument developed by Federal Library and Information Center Committee of Library of Congress (Library of Congress, 2008) were adopted and adapted for developing the questionnaires. In addition to that, several other measurements developed by previous studies, such as Buttlar & Du Mont (1996); Abriza (1998); Zaiton et al. (2004); Soo (2005); Griffiths (2005); Krissof & Konrad (2005); Lou (2007) and Rice-Lively & Racine (2008) were also referred to. The developed questionnaire used in the study measured seven aspects of competencies as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Aspects of Competencies Covered in the Questionnaire

Likert scale was used for all questions measuring competencies. The anchoring used was NR for “Not Relevant”; 1 for “Weak”, 2 for “Fair” and 3 for “Good”. Prior to actual data collections, the questionnaires were pre-tested and pilot tested with 30 library personnel at PUSTAKA Negeri Sarawak. Several questionnaires were also sent to library personnel at the Perbadanan Perpustakaan Awam Negeri Selangor. In the pilot study exercise, the participants were requested to evaluate and appraise the questionnaires in terms of content accuracy, clarity, length, and overall presentation. They were also encouraged to comment and criticize constructively. However, prior to the evaluation, all participants were briefed on the research questions, research objectives, scope and context of the study. Based on the feedback obtained from the pilot study, the researchers modified the questionnaire accordingly. The questionnaire was sent to every library personnel across all public libraries in Sarawak. However, out of 552 questionnaires that were sent, 507 were returned but only 502 were found useful. The remaining were either unreturned or unusable i.e. incomplete.

Findings

Demographic

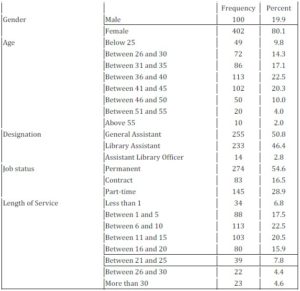

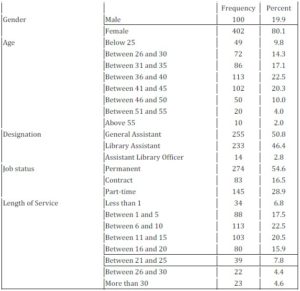

Table 3 shows the demographic profiles of respondents who participated in the study. Out of 502 respondents, 100 or 19.9% of the respondent were male, while the females were 402 or 80.1%. In terms of their age, the age group between 36 and 40 were the highest respondents which stood at 22.5%; followed by age group between 41 and 45 (20.3%) and age group between 31 and 35 (17.1%). The least number of respondents came from the age group above 55 (2.0%). With regard to their designation, 50.8% reported to hold the “General Assistant” post, while 46.4% indicated as holding the “Library Assistant” post. The remaining 2.8% responded as holding the “Assistant Library Officer” post. In this study, three categories of job status were reported by respondents, namely permanent, contract and part-time. Evidently, the majority of the respondents indicated that they were permanent staff (54.6%) while 28.9% and 16.5% indicated that they were part-time and contract respectively. Finally, in terms of their length of service, the highest number of respondents had been working for between 6 and 10 years (22.5%). The least number of respondents indicated to have been working for more than 30 years (4.6%).

Table 3: Demographic Profiles of Respondents

Required Competencies

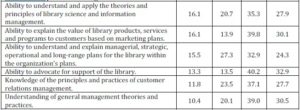

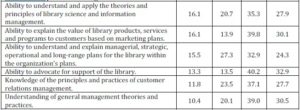

Table 4 illustrates the required level of general competencies measured in terms of percentage of responses. Overall, out of 22 listed competencies, 46.3% respondents indicated that required level of general competencies was medium, 38.2% respondents indicated that the required general competencies was high while 9.9% indicated that their level of general competencies was low. About 5.8% of the respondents responded that the listed general competencies were irrelevant to their current job. In terms of most required competency, the highest responses was ‘teamwork and collaboration’ (59.4%), followed by ‘interpersonal skills’ and ‘ethical framework’ which scored 52.4% and 50.4% respectively. In terms of the lowest required competency, the highest responses were ‘mathematical reasoning’ (20.5%), followed by ‘external awareness’ (14.7%) and ‘foundational knowledge’ (13.9%). With regard to competencies that are not relevant to their current job post, the three top scoring were ‘external awareness’ (14.7%), ‘mathematical reasoning (13.9%) and ‘leadership’ (12.7%).

Table 4: Required Level of General Competencies

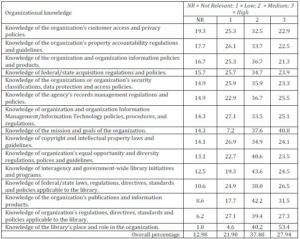

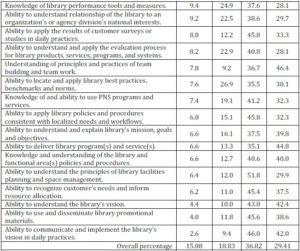

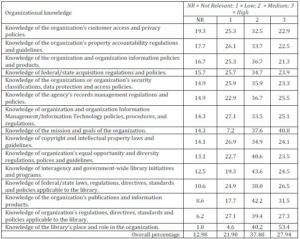

Table 5 exhibits the results of the required level of organizational knowledge competencies measured in terms of percentage of responses. Overall, the compositions of responses were 12.9% for ‘not relevant’, 21.9% for low, 37.4% for medium and 27.9% for high. In terms of the most required competencies, three highest responses were ‘knowledge of the library’s place and role in the organization’ (53.4%), ‘knowledge of the mission and goals of the organization’ (40.8%) and ‘knowledge of the organization’s publications and information products’ (31.5%). In contrast, the top three highest responses for moderate or medium required competencies were ‘knowledge of interagency and government-wide library initiatives and programs’ (43.6.2%), ‘knowledge of the organization’s publications and information products’ (42.2%) and ‘knowledge of organization’s equal opportunity and diversity regulations, polices and guidelines’ (40.6%). With regard to the lowest required competencies, the three top most responses were ‘knowledge of organization’s regulations, directives, standards and policies applicable to the library’ (27.1%), ‘knowledge of organization and organization Information Management/Information Technology policies, procedures, and regulations’ (27.1%) and ‘knowledge of copyright and intellectual property laws and guidelines’ (26.9%). The top highest responses for the irrelevant competencies were ‘knowledge of the organization’s customer access and privacy policies’ (19.3%), followed by ‘knowledge of the organization’s property accountability regulations and guidelines’ (17.7%) and ‘knowledge of the organization and organization information policies and products’ (16.7%).

Table 5: Required Level of Organizational Knowledge Competencies

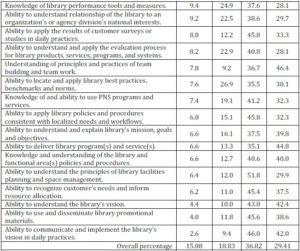

Table 6 showcases the required level of library leadership and advocacy competencies profiles of the respondents measured in terms of percentage of responses. Top three highest responses for the most required competencies were ‘understanding of principles and practices of team building and team work’ (46.4%), ‘ability to deliver library program(s) and service(s)’ (44.8%) and ‘the ability to understand the library’s vision’ (42.4%). In terms of moderate mediocre required competency level, the top three highest responses were ‘ability to understand the principles of library facilities planning and space management’ which recorded 51.8%, followed by ‘ability to communicate and implement the library’s vision in daily practices’ which stood at 46.0% and ‘ability to apply the results of customer surveys or studies in daily practices’ which recorded 45.8%. In terms of the lowest required competencies, the top three responses were ‘ability to understand the library’s Continuity of Operations Plan (COOP) and risk management program’ (31.9%), ‘knowledge of the role of alliances and collaborative relationships in program development and outreach’ (30.7%) and ‘knowledge and practices of outreach to existing and potential clienteles’ (27.9%). The top three highest responses for the not needed competencies were ‘knowledge of and ability to use staff training programs’ (29.7%), ‘ability to understand and use library licenses and other agreements’ (25.7%) and ‘knowledge of principles and practices of human resources management and labor relations in a diverse workforce’ (25.5%). Overall, the majority of respondents indicated that the required competency for library leadership and advocacy aspects was mediocre (36.8%). In contrast 15.0%, 18.8% and 29.4% responded that the competencies were not needed, low and high respectively.

Table 6: Required Level of Library Leadership and Advocacy Competencies

Table 7 depicts the findings of the required level of research and reference competencies for the Basic level measured in terms of percentage of responses. Based on the findings, it was discovered that majority of the respondents indicated that the required competency for the research and reference aspect was moderate (32.0%), while 23.4% indicated that the required skill was low and 23.6% was high. The remainder (21.1%) indicated that the competencies were not required with the current job. The top three highest responses of most required competencies were ‘ability to use the library’s existing reference and research products, services and programs’ (30.3%), ‘understanding of selection and dissemination tools and technologies for continuous information flow’ (27.1%) and ‘knowledge of current technologies and information resources’ (25.9%). The three highest responses for the moderate level were ‘ability to use the library’s existing reference and research products, services and programs’ (39.4%), ‘understanding of and ability to apply search strategies to retrieve information’ (37.8%) and ‘knowledge of current technologies and information resources’ (36.3%). The top three highest recorded least-needed competencies were ‘ability to understand and apply the principles of verification and evaluation of Information Resources’ (28.7%), ‘Knowledge of database structure and organization’ (28.3%) and ‘understanding of data mining techniques’ (26.9%). The top three responses for the not needed competencies were ‘understanding of data mining techniques’ (31.3%), ‘knowledge of reference and research principles and methodologies’ (31.1%) and ‘knowledge of the principles and practices of bibliographic instruction’ (27.3%).

Table 7: Required Level of Research and Reference Competencies

Table 8 shows the respondents’ required level of collection management competencies measured in terms of percentage of responses. The top three responses for the most required competencies were ‘understanding of the concepts and best practices of circulation and access to library resources’, ‘knowledge of the library’s acquisitions policies and procedures’, ‘knowledge of the concepts, principles and guidelines of library resource sharing’ which recorded 32,7%, 29.9% and 28.1% respectively. The top three responses for moderate-required level were ‘knowledge of the library’s acquisitions policies and procedures, ‘knowledge of the concepts, principles and guidelines of library resource sharing’,’ knowledge of the theory, principles, and standards and practices in the life cycle of library collections’ which stood at 35.9%, 35.5% and 35.5% respectively. The top three responses for least required competencies were ‘knowledge of theories, trends and practices of conservation, preservation, or archiving of resources’ (33.5%), ‘knowledge of disaster planning and the library and organization’s plan(s)’ (30.7%) and ‘knowledge of disaster planning and the library and organization’s plan(s)’ (30.3%). The top three responses for not needed competencies were ‘ability to understand and use resource sharing tools’ which scored 45.0%, followed by ‘knowledge of the licenses or agreements governing access to the library’s electronic collections’ and ‘knowledge of the publishing and information industry in relation to collection assessment and development’ which stood at 26.7% and 26.5% respectively.

Table 8: Required Level of Collection Management Competencies

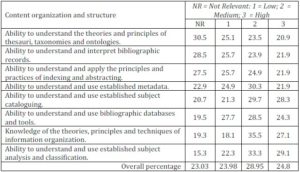

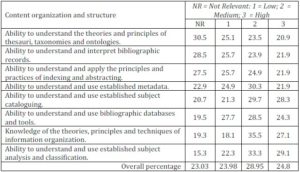

Table 9 presents the required competencies for the content organization and structure competencies measured in terms of percentage of responses. The ‘ability to understand the theories and principles of thesauri, taxonomies and ontologies’ was considered the most irrelevant competency, justified by the highest scoring of responses (30.5%), followed by ‘ability to understand and interpret bibliographic records’ and ‘ability to understand and apply the principles and practices of indexing and abstracting’ which recorded about 28.5% and 27.5% respectively. With regard to most required competencies, top three scorings were ‘ability to understand and use established subject analysis and classification’ (29.1%), ‘ability to understand and use established subject cataloguing’ (28.3%) and ‘knowledge of the theories, principles and techniques of information organization’ (27.1%). The three top highest moderate required competencies were ‘knowledge of the theories, principles and techniques of information organization’ (35.5%), followed by ‘ability to understand and use established subject analysis and classification’ (33.3%) and ‘ability to understand and use established metadata’ (30.3%). The top three responses in terms of least required competencies were ‘ability to understand and use bibliographic databases and tools’ (27.7%), ‘ability to understand and apply the principles and practices of indexing and abstracting ontologies’ (44.8%) and ‘ability to understand and interpret bibliographic records’ (25.7%). The overall scoring for the ‘not relevant’, ‘low’, ‘moderate’ and ‘high’ required competencies were 23.0%, 23.9%, 28.9% and 24.8% respectively.

Table 9: Required Level of Content Organization and Structure Competencies

Table 10 illustrates the findings of the required level of library technology management competencies measured in terms of percentage of responses. About 23.5% of the respondents answered that the required skills was low, 28.9% and 22.1% were moderate and high respectively. About 25.7% indicated that this set of competencies were not relevant in the context of their present job. Three top popular scorings for the most required competencies were ‘knowledge of library technology tools, trends and practices’ (27.5%), ‘ability to understand how customer needs impact information technology and management systems’ (26.1%) and ‘knowledge of performance measures for library systems and application’ (24.7%). Three highest percentages for the mediocre level of competencies were ‘knowledge of library technology tools, trends and practices’ (36.3%), ‘knowledge of the theories and practices of library and content management systems’ (35.3%) and ‘ability to understand how customer needs impact information technology and management systems’ (33.9%). With regard to the least needed competencies, three highest responses were ‘knowledge of data standards’ (28.7%), followed by ‘knowledge of systems analysis principles and techniques’ and ‘knowledge of standard performance measures for library technology applications’ which measured at 25.9% and 25.5% respectively. About 34.1% respondents also noted that ‘knowledge of the process of system certification and acceptance’ was not needed in their current job while 32.9% indicated that ‘knowledge of authentication protocols and their application’ was also not required.

Table 10: Required Level of Library Technology Management Competencies

Discussion

In determining the required competencies of the para-professionals in the library services, this study has developed a questionnaire which measures seven aspects of competencies, namely general competency; organizational knowledge; library leadership and advocacy; reference and research; collection management; content organization and structure and library technology management. Among the seven listed competencies, the general competencies scored the highest, suggesting that it is the most sought after competencies among these para-professionals. The general competencies include mathematical reasoning; leadership; listening skills; conflict management; self-management; problem solving; interpersonal skills; decision making etc. These general competencies which can be considered as the fundamental competencies are the common competencies needed by almost all professions. Famous competencies models developed by researchers have apparently incorporated these competencies into their models.

The lowest required competencies reported by respondents are the library technology management competencies. These competencies which measure, among others, skills and knowledge on systems analysis; information infrastructure; data standards; library content management systems; library technology tools and practices etc, may not be very relevant and appropriate to some of the respondents as their workplace is located in quite a rural area and furthermore, the facility and the nature of their work does not require them to practice such competencies. Perhaps, due to this reason, the library technology management competencies recorded the lowest scoring among the seven listed competencies.

Other than the general competencies and the library technology management competencies, the scoring of all other competencies is almost identical, which can be considered as moderately needed or required. Given that the environment of the respondents’ workplace which is very diverse with some working in the urban areas, others working in rural areas, the nature of the required competencies could be different. Likewise, the type of library that these respondents are serving also could be an influential factor. As for those who work in the rural library where the facility is not as extensive compared to the state library, the need for technology-related competencies may not be very demanding. On the other hand, in the state libraries or any other libraries located in the urban part where the libraries are far better equipped with ICT facilities, the need of technology-related competencies could be very demanding. The demographic profiles of the community using the library services could also be an important factor. In a rural library settings, where most users are not well exposed to ICT related services, the need to have human-related competencies would be far higher compared to urban settings.

Conclusion

The conduct of this study has been to investigate the required competencies among para-professionals in the library services in the state of Sarawak, Malaysia. The findings of this study suggest that the competencies needed by the para-professionals are almost identical to the competencies of the professional librarians which incorporate general competency; organizational knowledge; library leadership and advocacy; reference and research; collection management; content organization and structure and library technology management. The findings of this study will help the authorities concerned to identify the training needs required by these para-professionals. In addition, academic institutions offering library management programs will also find the findings to be useful when devising their curriculum. Just as in other studies, this study is not without limitations. Firstly, the study used perceptual measures to gauge respondents required competencies. In addition, the questionnaire is also very lengthy which to some extent affect the concentration of the respondents when answering. These limitations can be exploited by future researchers, in case they intent to conduct similar study.

Acknowledgement

The researchers would like to extend their thanks and gratitude to Pustaka Negeri Sarawak for funding the project.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

Abdullah, A. (1998). “Competencies for Teacher Librarians in Malaysia,” Dissertation (M.L.I.S.) Fakulti Sains Komputer dan Teknologi Maklumat. Kuala Lumpur: UM.

Publisher – Google Scholar

American Library Association. (2009). “ALA’s Core Competencies of Librarianship,” [Online], [Retrieved January 21, 2012] http://www.ala.org/educationcareers/careers/corecomp/corecompetences

Publisher

Ashcroft, L. (2004). “Developing Competencies, Critical Analysis and Personal Transferable Skills in Future Information Professionals,” Library Review, 53 (2), 82-88.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Blaikie, N. W. H. (2003). Analyzing Quantitative Data: From Description to Explanation, Sage Publications, London.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Braun, L. W. (2002). “New Roles: A Librarian by Any Name,” Library Journal, 127 (2), 46-49.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Buttlar, L. & DuMont, R. (1996). “Library and Information Science Competencies Revisited,” Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, 37(1), 44-62.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Cheetham, G. & Chivers, G. (1996). “Towards a Holistic Model of Professional Competence,” Journal of European Industrial Training, 20(5), 20-30.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Competencies for special librarians of the 21st century: Library and information studies programs survey: Final report. (1998). Washington, DC: Special Libraries Association.

Cronin, B. (1983). “The Transition Years: New Initiatives in The Education of Professional Information Workers,” Aslib, London.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Eells, L. L. & Jaguszewski, J. M. (2008). “IT Competence for All: Propel your Staff to New Heights,” Technical Services Quarterly, 25(4), 17-35.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

FLICC (2008). “The Federal Library and Information Centre Committee Library of Congress,” [Online], [Retrieved January 21, 2012] [http://www.loc.gov/flicc/whatsnew.html

Publisher

Goulding, A., Bromham, B., Hannabus, S. & Cramer, D. (1999). “Supply and Demand: The Workforce Needs of Library and Information Services and Personal Qualities of New Professionals,” Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 31(4), 212-223.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Griffiths, J. (2005). ‘New Directions In Library And Information Science Education,’ Greenwood Press, Westport CT.

Griffiths, J.- M. & King, D. W. (1985). New Directions in Library and Information Science Education, Greenwood Press, Westport, CT.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Helmick, C. & Swigger, K. (2006). ‘Core Competencies of Library Practitioners,’ Public Libraries, 45(2), 54-69.

Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Huber, J. T. (1995). “Library and Information Studies Education for the 21st Century Practitioner,” Journal of Library Administration, 20(3/4), 119-130.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Kenny, D. A. (2008). “Reflections on Mediation”, Organizational Research Methods, 11, 353-358.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Krissof & Konrad (2005). ‘Managing the 21st Century Reference Department: Competencies,’ Reference Librarian, 81, 35-50.

Lester, S. (1995). “Beyond Knowledge and Competence: Towards a Framework for Professional Education,” Capability, 1(3), 1-10.

Publisher – Google Scholar

Lou, C. (2007). ‘Identification of Competencies for Professional Staff of Public Libraries,’ Public Library Quarterly, 20 (1), 17-43.

Musher, R. (2001). “The Changing Role of the Information Professional,” Online, 25(5), 62-64.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia. (2004). ‘Laporan Kajian Identifikasi Dan Analisis Jurang Kompetensi Pustakawan Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia,’ National Library of Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur.

Rice-Lively & Racine (2008). ‘The Challenge of Developing a Competence-Oriented Curriculum: An Integrative Framework,’ Library Review; 53(2), 98-103.

Schroeter, K. (2008). Competence Literature Review, Competency & Credentialing Institute, Denver.

Publisher

Soo-Guan Khoo. (2005). ‘Competencies for New Era Librarians and Information Professionals,’ Library Review, 53(2), 74-81.

Google Scholar

Vakola, M., Soderquist, K. E. & Prastacos, G. P. (2007). “Competency Management in Support of Organizational Change,” International Journal of Manpower, 28(3/4), 260-275.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Vitala, R. (2005). “Perceived Development Needs of Managers Compared to An Integrated Management Competency Model,” Journal of Workplace Learning, 17(7), 436-451.

Publisher – Google Scholar – British Library Direct

Yaszay, B., Kubiak, E., Agel, J. & Hanel, D. P. (2009). “ACGME Core Competencies: Where are We?,” ORTHOPEDICS [Online],[Retrieved January 21, 2012] http://www.Orthosupersite.com/view.asp?rid=37208

Publisher

Zaiton Osman et.al. (2004). ‘Laporan Kajian Keperluan Sumber Manusia Dalam Bidang Perpustkaan Dan Perkhidmatan Maklumat Di Malaysia,’ National Library of Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur.